The Covid-19 pandemic, and the lockdown of the UK, has resulted in an unprecedented economic crisis. The impacts are acute and widespread, and the future is uncertain.

Local authorities have been, rightly, focusing on the immediate response to the crisis, delivering significant elements of the UK Government’s business support package as well as responding to the huge challenges of delivering social care and supporting vulnerable people. Towns, Cities and Combined Authorities are now focusing on the economic recovery phase, for example the Core Cities Group have recently published proposals to give cities the powers and resources they need to boost the recovery.

This is a big agenda. I suggest seven calls to action for how towns, cities, local authorities, Combined Authorities and LEPs can put in place the building blocks to kick-start and build more resilient, inclusive and productive economies as we emerge from the Covid-19 crisis.

First, start working on the recovery plan now. Whilst there is an urgent focus on the immediate crisis response, business also needs confidence about that there is a medium-to-longer term economic plan in place. There is a need to put in place capacity to think and act on how we can put in place the right building blocks to try to make this a V-shaped recovery. This work needs to be prominent and visible.

Second, plan for the exit from lock-down and a new test-trace-isolate phase. Cities and towns will need to retrofit their transport systems (i.e. ensuring public transport is not overcrowded, or reallocating road space to pedestrians) and buildings to enable this. Agent-based modelling tools can provide a valuable resource in understanding how space is used, and how people interact.

Third, local authorities, combined authorities and LEPs need to shape and help deliver a major economic stimulus package of regeneration, infrastructure, housing and economic growth projects to kickstart economic recovery. Think a modern-day equivalents of the post war Marshall plan. This should include keeping existing projects moving, and identify new ones. It could require bold interventions in the property market to kick-start stalled schemes, and as Jackie Sadek has set out, Homes England have a major role to play. As Neil O’Brien MP has stated, the biggest economic impact of the COVID-19 recession seems likely to be in the North and Midlands, so the levelling up mission is more important than ever.

Fourth, we need local initiatives to back innovators and entrepreneurs and existing firms seeking to pivot. The Save Our Start-Ups campaign has highlighted the impact of the crisis on innovation-driven start-ups and scale-ups. These high growth businesses, which make a huge contribution to the economy through their investment in people, technology and innovation, are likely to find securing finance harder, and many will not qualify for the UK Government’s Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBILS). The Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, has announced a significant package of support to address these gaps.

Cities and local authorities can connect innovators, entrepreneurs, the health and social care system and other providers of public services to work together to tackle societal and health challenges. For example, this approach is a cornerstone of the strategy we are developing in Leeds City Region through the MIT Regional Entrepreneurship Acceleration Programme. This could be part of a wider mission-orientated approach to supporting innovation-driven economic growth. A £20 million competition launched by Innovate UK to support firms responding to new and urgent needs as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. There is also a need to provide support and finance to firms facing growth or investment pressures in responding to new markets and demands, for example for home deliveries, medical equipment, and online services.

Fifth, Work on re-imagining town and city centres should gather pace. The crisis is accelerating the shift from “bricks to clicks” in retail, and the leisure sector has been hit hard. There will be a need to be bold and re-imagine the role of retail and leisure centres fundamentally.

Sixth, this crisis is going to lead to a huge shake-out in the labour market. Cities, local authorities and LEPs / Combined Authorities have a pivotal role in mobilising the skills system to help people gain new skills and connect them to jobs. This should include connecting people who have lost their jobs from the worst affected sectors (ie. Hospitality, tourism) with those in sectors experiencing growth (healthcare, deliveries and logistics, IT). There will need to think about and mitigate the impact on youth unemployment / underemployment.

Seventh, cities can learn from this crisis to build a different economy. The recent shifts in working practices could used to demonstrate that actions to tackle climate change are possible. Volunteer networks to support vulnerable people could be maintained. We need to think about how best we can strengthen support for key workers and people in less secure jobs, and put in place more initiative like Wakefield’s Step-Up project, to support people to progress out of low-paid, insecure jobs.

Finally, a historic perspective is important here.

Will Covid-19 mean the end of cities? Almost certainly not, for the reasons set out in this article by Joe Cortright.

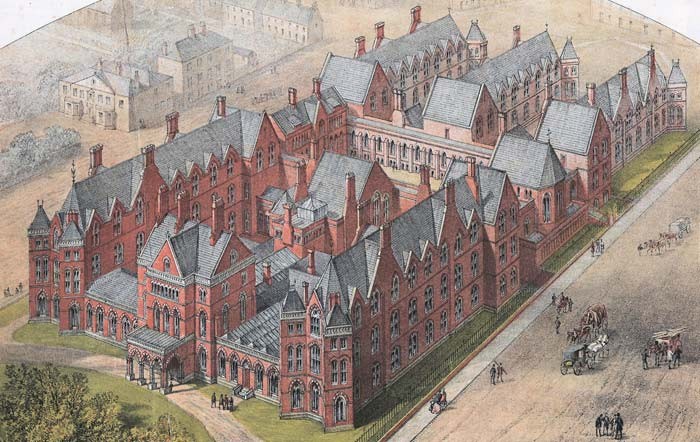

As Ed Glaeser has written, cities and pandemics have a long history. Throughout history, cities and towns have needed to strike a balancing act between providing the densities that support the collaboration, knowledge and innovation needed to accelerate economic growth, whilst also addressing the public health risks that density creates. In 1854 John Snow meticulously mapped the London cholera outbreak, identifying the source (a water pump). The Victorians built sanitation systems and hospitals (Florence Nightingale advised on the design of the new Leeds General Infirmary that was opened in 1869), and in the post war period our cities built and improved public housing on a huge scale. We are now going to need to adapt our cities once again.

After 9/11 many commentators predicted fundamental changes in urban areas, for example a shift away from tall buildings, and global travel. Instead we adapted our cities and transport networks with security measures to respond to the new normal.

With the growth of the internet and global communications, many predicted the death of cities and densities – why commute and cluster in urban centres when we can communicate from our homes? In reality, as the economy has become more specialised, knowledge based and focused on intangibles, face-to-face proximity has become more, not less important. Smart people want to work alongside other smart people, they want to collaborate, compare and compete in the spaces between the buildings, and they value access to a large concentrations of employment so they can move job without moving house. Knowledge producing firms and institutions want to be close to each other and have access to a skilled and creative workforce across a wide area. Urban innovation districts are emerging and some of the most dynamic engines of economic growth. All of this is supported by public transport networks, the right supply of commercial space, and the curation of networks between corporates, start-ups and scale-ups, universities and major cultural institutions, investors, and city governments.

The experience of the last few weeks has demonstrated to many of us the inefficiencies of mass working from home: the challenges in collaborating across disciplines and organisations, the difficulties in building the relationships and implicit trust that come from face-to-face discussions, the sheer time and energy required to run a Zoom meeting compared to a physical one, the monotony of staring at a screen, the loneliness and lack of fun and enjoyment. I predict that this experience will re-enforce the need for firms to have the right office space in urban areas. They may need less of it, and its primary function may shift towards supporting collaboration and away from providing banks of desks. And we will want to interact, to share ideas, and to share each other’s company in urban places – albeit cautiously and at a distance at first.

Whilst our towns and cities will be different as a result of this crisis, they will be central to the huge economic recovery effort needed. Urban density can support the innovation and access to opportunities needed as part of the economic recovery, as well as helping us tackle huge challenges such as housing supply and climate change. As Ed Glaeser has argued, “We have built our modern world around proximity, and Covid-19 has made the costs of that closeness painfully obvious. We can either reorient ourselves around distance or recommit ourselves to waging war against density’s greatest enemy: contagious disease.”

The challenges are significant. They will be exacerbated by the acute budget pressures local authorities are facing as a result of this crisis and a decade of austerity. Local leaders and their economic development teams have a huge role to shape and support this recovery, and to build better, fairer, more resilient, sustainable and productive economies.

Tom Bridges

Leeds Office Leader and Director Cities Advisory at Arup

(Taken from an article published on LinkedIn April 2020)